or, How Setting Makes a Story

Editing a good dissertation is like auditing a class, and as a person who was deported from the land of academia for taking four years to obtain a two-year master’s degree, I love that. Last Thanksgiving I expressed my gratitude for the grad students who hire me to polish their dissertations. Not only do they provide an income stream, but they bring me new ideas, lofty academic stuff that I don’t run across in my day-to-day. Bonus: I get the best of the class without having to leave my house or listen to That Guy who monopolizes every discussion. You remember That Guy.

Anyway, this year’s student introduced me to Félix Guattari, Marxist poststructuralist psychoanalyst, and his three ecologies: those of mind, society, and environment. He’s involved with the deep ecology movement, but that’s not what I’m interested in right now. Reading this student’s research made me think about the importance of setting in any narrative.

Let’s break it down freshman style: ecology derives from the Greek roots oîkos, meaning “house,” and logía, “the study of.” It is the science of where we are now and how that affects us. Biology and environmentalism are generally where people go with that, but we can transfer the concept to storytelling.

Creator of Worlds

For me, the hallmark of a good story, fiction or nonfiction, told with print or film or stage, is that it creates a world that lingers in memory long after the story has come to an end. A key element of this world building is setting. One could argue, and I do, that setting is as important if not more so than characters. In a sense, it has to be a character in whatever narrative you are telling. The audience needs to understand its backstory, its traits, and why it reacts in predictable or unpredictable ways as events unfold.

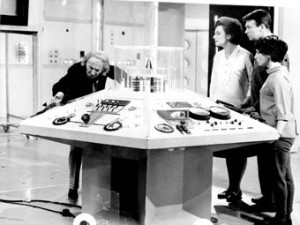

To use a negative example, have you ever watched episodes from original Star Trek or early Doctor Who in which the characters are trapped in some featureless landscape or a tiny room? This may have been edgy in the 60s, but now it qualifies as blunt force trauma. It’s claustrophobic, tedious, and more or less unwatchable unless you’re a hardcore fan. This is what happens when you subtract a sense of place that is connected to an individual (mind), a group (society), and a physical location (environment).

How do I make my setting (and story) unforgettable?

So glad you asked! Setting needs to have a connection to character and events. You can’t just toss your characters into a primeval forest or an overgrown building in Chernobyl or an underground factory in a dystopian future or a ratty apartment in the Lower East Side in the 30s—not without knowing why they are there and why this is either the best or the worst possible place for these characters to be at this time. Note that last word, time. When is part of where. It gives dimension to setting.

Frequently characters arrive in a writer’s brain with their time and place fully intact. If not, you may need to chat with them for a while, observe them as you would strangers in a train station. What are they wearing, how do they speak? What do they carry? Urban, rural, wealthy, poor, from the past, from the future? Sheltered, worldly, street smart? Are they comfortable wherever they find themselves? Are they fish out of water no matter where they go? Do the distinct places from which two characters come create a conflict between them, a disconnect?

If you are working in the genre of fantasy, you have both immense freedom to invent ecologies and immense responsibility to create the perfect place for your story because the limits of our space and time don’t exist. Use your powers wisely, and don’t trap your characters in a box when you have the universe at your disposal.

A Little Bit of Not-Here

A final note on setting: no matter how bleak their current surroundings, characters must all carry some piece of sanctuary, some memory or talisman or dream of a better future to represent the hope they have of getting out of there. That idea or item signifying a better place creates contrast with the present; without it, the setting is flat and offers no connection to the audience or the characters. Just as you need ebb and flow in the steady rise of emotional engagement, there needs to be variety in setting. When you build your house, give your characters light and shadow to play in.